SPONSORED: This post is presented by the Toyota RAV4 EV. Because innovation can be measured in miles, kilowatts and cubic feet. Learn more at toyota.com/rav4ev

Alexander Calder with [Paul] Matisse and a maquette of his last mobile. The maquette was enlarged 40 times in the final piece. (Source: Alexander Calder Special Collection Photo)

Alexander Calder's (1898-1976) father was Alexander Stirling Calder (1870-1945), who sculpted George Washington as President on the Washington Square Arch in New York. His grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder (1846 – 1923), sculpted the 37-foot tall William Penn statue, which stands atop Philadelphia City Hall. His great-grandfather was a tombstone carver.

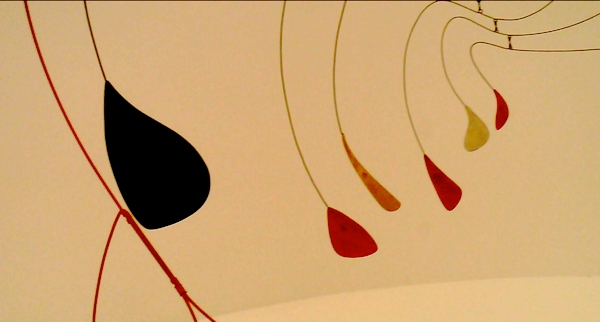

So it's not surprising that Calder become a sculptor as well. But unlike his forebears, Calder was not interested in traditional sculpture. Instead, he invented a new art form — kinetic sculpture — the most famous of which were his "mobiles," (a word coined by his friend, the artist Marcel Duchamp). These delicately balanced sculptures consist of biomorphic shapes cut from sheet metal and painted in black, white, orange, red, white, yellow, and blue, and which hang from metal rods and wire.

So it's not surprising that Calder become a sculptor as well. But unlike his forebears, Calder was not interested in traditional sculpture. Instead, he invented a new art form — kinetic sculpture — the most famous of which were his "mobiles," (a word coined by his friend, the artist Marcel Duchamp). These delicately balanced sculptures consist of biomorphic shapes cut from sheet metal and painted in black, white, orange, red, white, yellow, and blue, and which hang from metal rods and wire.

Calder's innovative use of materials, gracefully moving mobiles, and startlingly unique stabiles led to Calder becoming one of the most famous artists of all time. In the 1970s no major city was complete without a giant-sized Calder stable on permanent display. His work "shatters the illusion of everything that sculpture ever was," said Arne Glimcher, the chair of the Pace Wilderstein Gallery. "It is unlike any body of work created this century."

Calder's innovative use of materials, gracefully moving mobiles, and startlingly unique stabiles led to Calder becoming one of the most famous artists of all time. In the 1970s no major city was complete without a giant-sized Calder stable on permanent display. His work "shatters the illusion of everything that sculpture ever was," said Arne Glimcher, the chair of the Pace Wilderstein Gallery. "It is unlike any body of work created this century."

This weekend Carla and I went to a terrific Calder exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern art. On display were dozens of his mobiles and stabiles (stationary abstract sculptures).

This weekend Carla and I went to a terrific Calder exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern art. On display were dozens of his mobiles and stabiles (stationary abstract sculptures).

As I admired the sculptures, I wondered how Calder was able to get his mobiles to balance.

As I admired the sculptures, I wondered how Calder was able to get his mobiles to balance.

I looked closely at the way Calder attached the pieces of his mobiles, because I wanted to try making a mobile when I got home.

I looked closely at the way Calder attached the pieces of his mobiles, because I wanted to try making a mobile when I got home.

The first thing I did was draw a bunch of biometric shapes on a sheet of corrugated cardboard. Then I cut them out with a snap-blade knife.

The first thing I did was draw a bunch of biometric shapes on a sheet of corrugated cardboard. Then I cut them out with a snap-blade knife.

Using the same sheet of cardboard, I cut out pieces for a base and glued them together.

Using the same sheet of cardboard, I cut out pieces for a base and glued them together.

I used coat hanger wire to connect the cardboard shapes together.

I used coat hanger wire to connect the cardboard shapes together.

It took a lot of fiddling to get the thing to balance. I was able to manage it by repositioning the cardboard on the wire, and by snipping off pieces of cardboard. My Calder rip-off is ugly and ungainly compared to the real thing, but I enjoyed making it, and feel like I got a bit of insight into his process. I looked for a video that showed Calder at work, but I couldn't find one [Update: Marco Mahler found one!]. I'd love to see him making his art.

It took a lot of fiddling to get the thing to balance. I was able to manage it by repositioning the cardboard on the wire, and by snipping off pieces of cardboard. My Calder rip-off is ugly and ungainly compared to the real thing, but I enjoyed making it, and feel like I got a bit of insight into his process. I looked for a video that showed Calder at work, but I couldn't find one [Update: Marco Mahler found one!]. I'd love to see him making his art.

A short video of Calder's mobiles.

The above movie, Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947), is an avant garde film that has Calder's mobiles and his incredible animatronic wire circus. (This version of the movie has crappy overdubbed music, but it's worth watching nonetheless).

Works of Calder on Nowness.com

The Works of Calder shows the artist at work, but not balancing the mobiles. Nevertheless, it's a terrific film!