High Design.

David Pescovitz interviews the designer of Terrafugia's flying car

In the world of design, urban mobility is much more than how you get from point A to point B.

Urban mobility operates at the intersection of myriad innovation freeways, from architecture to infrastructure, technology to transportation, city planning to style. It's about feet, fashion, bikes, busses, automobiles, and yes, even cars that fly. For my longtime friend Jens Martin Skibsted, a Danish industrial designer, urban mobility is a fertile ground for experimentation. In 1998, Skibsted founded Biomega, a luxury bicycle brand whose unique two-wheelers are in the collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art and the SFMOMA. In recent years, Skibsted has brought his urban mobility mindset to Puma, designing an entire line of sharp city bikes that fold up or feature bike locks integrated into the frame. Indeed, he's even created a Puma bike sneaker to wear when pedaling.

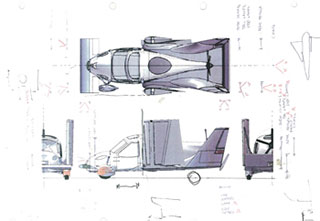

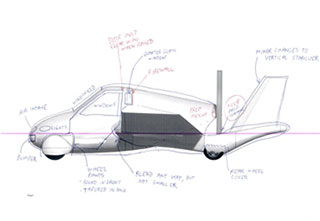

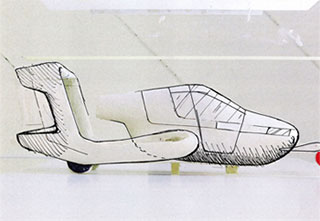

Recently, Skibsted and his partners in the KIBISI design studio have taken a less grounded look at the future of urban mobility when they were asked by Woburn, Massachusetts-based Terrafugia to redesign their flying car. The result, Terrafugia's next-generation Transition Roadable Aircraft, was unveiled on Monday. The Federal Aviation Administration is on board, having granted an addition 110 pounds within the Light Sport Aircraft category so that the Transition can integrate typical safety features found in cars. A scale model is now under construction and reservations are accepted for $10,000 with delivery planned for late next year. Previously, Terrafugia announced that the sale price would be in the $200,000 range. I spoke with Skibsted about the unique design challenge of building a car that flies. Or is it a plane that drives?

How did this project, er, get off the ground?

Tony Bertone, who is Puma's chief marketing officer, is a great friend and for some reason, when it comes to transportation he thinks I'm the guy to call. He invested in Terrafugia and had told the owner that I should be brought in as a designer. The original Terrafugia vehicle looked like an old James Bond aircraft and they realized that you can't make something that looks like that and still get it sold. While I was at TED two years ago, I talked on the phone with Terrafugia's CEO Carl Dietrich and discussed the project. Around that time, I had also started working with two other guys, the architect Bjarke Ingels, who spoke at TED, and Lars Larsen who had done electronics and furniture. We all had very different capabilities, and the plane was the first thing we worked on together. Talk about a flying start.

I'd imagine that designing a flying car is a unique challenging project.

Although KIBISI likes working on concepts for unusual objects and designs, this is not one of those things. This is a real vehicle that needs to fly. Usually, you have designers ping-ponging ideas with engineers. But this project had three stakeholders: us as designers, mechanical engineers, and then the aerodynamics engineers. Not only did we have back and forth between both of those groups, but at the same time they were battling with each other. For example, the mechanically cool engine might make the plane too heavy to fly. On top of those teamwork dynamics was always the question of whether is this a car or a plane? Or is it something else entirely? We ended up where it's mostly a plane.

What were some of the approaches you took?

In the end, we had 3 different design directions that we brought to Terrafugia. One was very plane-like, one that was much like a car, and a third that looked a bit like a helicopter. That was just far too strange though. Some of the company's engineers wanted the design to be very Testosterone-driven, but we thought that look wouldn't be particularly inviting. So we took it more toward the direction of a Volkswagen, so there's at least a bit of familiarity and the feeling that the machine is trustworthy.

How limited were you in the design choices you had?

This project has not been about aesthetics. We've brought a holistic view, but the aesthetic has to be in the background. Terrafugia is a start-up and has start-up challenges and limited resources. One of the ways to deal with that is to use standard parts to bring down costs. So therefore, we didn't have the option of designing the coolest headlights, for example, because we'd need to source those. So we focused on how to create an architecture where all of the components fit together, lines that go through everything, an inherent order where everything falls into place naturally. Terrafugia is a company of engineers. The management are engineers. The press people are engineers. The designer is an engineer. So the focus was on functionality. And since there are layers of engineers, it's hard for them to see the forest for the trees. Our job was to give them the picture of the forest.

Now that you've designed such a quintessentially futuristic machine, what's next?

Our dream would be to design an electric car. Most watches are made by watch designers, so that's why they all look alike. This is also the same with cars. Now things are being shaken up and we have a chance to reinvent the topology. It's a good time to bring in new people with fresh ideas from the outside to the auto industry. To all industries.