We may ask why the US sends troops abroad, but the fact is that we do send large numbers into a region about which they have little knowledge and almost no cultural connection. We then ask them to interact safely and efficiently with military and civilian natives. These interactions require varying levels of linguistic, cultural, and interpersonal background. As a foreign language educator, I am fascinated by the evolution of the training materials given to US soldiers and how cultural visual knowledge plays and increasingly important role.

Over the past seven years, the military has noticeably changed how it trains soldiers for these vital kinds of cross-cultural interactions. These "changes in visuality" allow an exemplary look at how visual & cultural literacy has seriously impacted language and cultural training.

The first way instructors train is to rely on a simple visual clue for meaning. This is the equivalent of simple translations. The approach image = word = meaning is effective when it comes to teaching soldiers basic life saving skills in the field while trying to increase their visual perception performance. In the case of IED recognition, nuance is not necessary and soldiers react quickly, based on what they see, to avoid this threat. Images of various IED types are presented for soldiers to study with the basic word association of IED = Death. The training materials also feature severed limbs to show the result of these attacks.

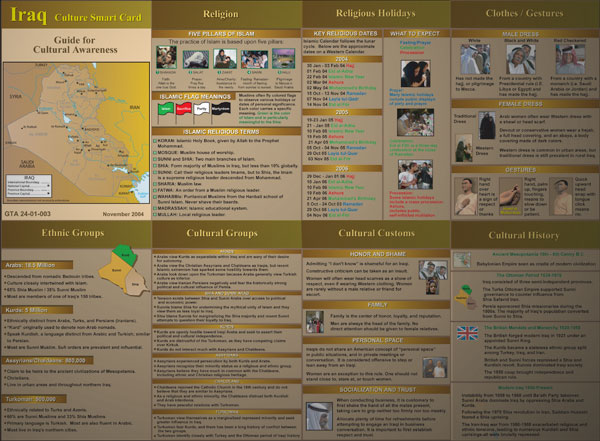

In highlighting cases like these we need to keep in mind the importance of the elementary nature of this survival training. Important vocabulary items were usually handed out on so called "smart cards" or laminated sheets for people to study with a limited amount of material on them. An almost complete reliance on visuals proved to be somewhat effective in the arena of threat recognition. When soldiers face the danger of improvised explosive devices, they need to visually recognize the object immediately. Additionally, they need to quickly identify their target in conditions that may not be optimal. Soldiers are increasingly using technology-mediated visual equipment, for example night vision, and must quickly make decisions based on visual clues alone. Beyond the mere threat recognition strategies associated with visual training of soldiers, a problem with 'enhanced' visual perception devices is the avoidance of fratricide as indicated in this 2008 study.

In the Iraqi and Afghani combat zones, however, the initial war was a precursor to the real war, that of the insurgency. The initial fighting gave way to an occupation involving an insurgency coupled with a civilian population that may or may not be hostile. Soldiers were not only expected to make decisions regarding friend or foe, they were expected to engage locals in close quarters with both weapons and words. The military also relied heavily on these visual training modules to equip their soldiers with linguistic and cultural knowledge.

The classic military phrase book method puts the locals in a clear adversarial position. All the phrases introduced center around providing security for the soldiers and keeping them alive. From that starting point, basic cultural knowledge is introduced including local customs, expressions, and items that one might encounter in the field. Here we see the progressions of two separate training cards for soldiers at two different stages. The second card moves towards authentic photos to instruct the soldiers in basic culture in Iraq, as the stick figure drawings were not providing enough useful information.

Cultural training materials developed from mere tools of threat recognition to models of threat prevention. The method of threat prevention is based on understanding the authentic culture of the area in order to engage the locals in a meaningful way. At Fort Irwin, California, at the National Training Center, the military has constructed Iraqi villages in the desert so soldiers can practice their interactions with locals and insurgents and get the authentic feel for life in Iraq as an occupying force. The documentary film Full Battle Rattle (2008) chronicles soldiers' experiences in this virtual arena where they are expected to engage people through culture and language, not merely through the force of their weapons.

This shift in approach has proven to be effective. Cultural training programs are ongoing and exist for several areas. Cross-cultural competence is "something that we want to bring to the department as a critical piece of training that we think needs to be incorporated into our overall training establishment," said Gail H. McGinn, the deputy undersecretary of defense for plans, during an interview with Pentagon Channel and American Forces Press Service reporters. This cultural training program has now gone electronic through the program "Tactical Language Series," a type of virtual reality gaming environment designed to teach people visual literacy and cultural knowledge for the geographical and linguistic areas in which they will serve. The company that developed the Tactical Language series, Alelo, Inc, states on their web site:

DARPA The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency Program Manager Dr. Ralph Chatham was inspired to start the program after listening to one of the first soldiers who went into Afghanistan in 2002. The captain told how he and his comrades reluctantly rode on tiny ponies into a town, totally relying on their Northern Alliance escorts who only spoke Pashto and some broken Russian and Arabic while the U.S. soldiers only spoke English and some broken Russian and Arabic. When the town's people came out on the streets the soldiers did not know if they were friendly or hostile from their gestures, demeanor and words.

The Tactical Language Series currently has virtual worlds for military personal to learn Iraqi Arabic, Pashto, Dari, and French for North Africa. Here you see examples from the "Tactical Iraqi" October 2009 release. These programs use a hybrid approach to training that employs authentic visuals and mission-based skills. Most importantly, though, cultural competence is taught through virtual engagement with locals. The program teaches soldiers to recognize military insignias of foreign militaries through virtual reality games designed to enhance their visual perception. Most of the training here takes places at a cognitive visual level, so that recall time is enhanced. Soldiers take commands in the local dialect and navigate virtual authentic cities and villages. They learn local customs, gestures, and cultural practices that are meant to help them interact with locals in order to avoid cultural misunderstandings.

This training software resembles the typical first person shooter game many soldiers are familiar with. Unlike a first person shooter game, though, this series does not have the option to pull a gun. In place of weapons one finds culturally-appropriate gestures and an accurate voice recognition system, which allows the learner to interact with virtual Iraqis in Arabic.

The development, implementation, and continued use of this intercultural training approach poses several questions.

What does this teach us about how we learn languages and interact with other cultures? In a short period of time (from an educational-curricular perspective) the military has gone from the old "Hands-up!" phrase book to a complete realization that culture is intrinsically tied to language and that phrases are not enough to engage people. In order to communicate, you must know something about a person. While it may not be a magic bullet for intercultural training, the fundamental design aspects of this educational training tool focus on cultural proficiency and use of the language in an authentic, respectful context.

From the Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) perspective, this training program highlights the fact that images, specifically culturally authentic images are required in this training. When you train absolute beginners, authentic images tie the language to a culturally specific context for use. For too long we have used generic stock photos, clip art, and line drawings for visual clues in multi-media learning environments. Since the greatest source of these images in the US, most of the world's computer based language programs reflect a world view (literally) that shows homes as always having a two car garage, white picket fences, grocery store baggers, and upper middle class citizens. You could say that clip art and stock photos are not representative of any culture. Nevertheless, they remain popular in popular language learning software packages.

In the educational world, we talk of assessment to prove educational effectiveness. In the world of the U.S. Military, assessment of cultural training can be a life and death matter. Therefore it is an interesting example from which we can learn a great deal. Alelo, Inc is developing software for the US Military that is, educationally speaking, pretty advanced and quite effective for elementary learners with little experience in language acquisition. The necessity of that training aside, it is fascinating to see a US military training program that sets out as its premise the need for threat avoidance through cultural understanding and linguistic proficiency. If one looks at the suggested pre-deployment reading list, one will find a great deal about the culture of the area, a shift from the previous approach of phrases and limited cultural information. Since NATO forces will adopt some of these technologies in the near future, specifically the UK and German forces, it is also fascinating to see the US take the lead on language learning.

What is the word for someone who speaks three languages? "Trilingual"

And the word for a speaker of two languages? "Bilingual"

And for one language? "American"

Perhaps the old joke may not be true anymore.

While the lessons of war are often lost on current and future generations of citizens, soldiers, and leaders, I'm hopeful that this method of using authentic media in an effective & prudent manner will be one to reach language educators at all levels of instruction. The media is out there, so let's use it in a better way.